Ever stared at a Japanese kanji character and wondered why it has multiple pronunciations? You're not alone! The struggle between onyomi vs kunyomi is real for every Japanese learner. One minute you're confidently reading 山 as "yama," and the next, you're seeing it in a compound word pronounced as "san."

What gives? Well, I guess that just shows the fascinating (and sometimes frustrating) world of kunyomi vs onyomi readings.

In this post, I'll break down everything you need to know about these two reading systems. We'll explore where they came from, when to use each one, and practical tricks to remember them. By the end, you'll have a clear roadmap for tackling one of the trickiest parts of learning Japanese kanji without losing your mind.

- Learn the Japanese Alphabet: A Guide to Hiragana (Part 1)

- Learn the Japanese Alphabet: A Guide to Katakana (Part 2)

- Learn the Japanese Alphabet: A Guide to Kanji (Part 3)

What Is On'yomi And Kun'yomi?

The story of kanji in Japan begins around the 4th century when there was no writing system in Japan. Japanese was only spoken, not written. Meanwhile, China had already developed its writing system called "hanzi" (漢字).

Japanese scholars, monks, and officials who traveled to China or studied Chinese texts brought these characters back to Japan. They faced a huge problem: Japanese and Chinese are completely different Asian languages with different grammar, vocabulary, and sounds. They already had their own language with words for things like "water," "mountain," and "tree."

Instead of creating a new writing system from scratch (which would come later with hiragana and katakana), they decided to adapt the Chinese characters to write Japanese. This created a unique situation:

- On'yomi (音読み): The Chinese-derived pronunciation

- Kun'yomi (訓読み): The native Japanese pronunciation

What makes things more complicated is that Japan didn't import kanji just once. They borrowed characters during at least three major periods when Chinese pronunciation itself had changed:

- Go-on (呉音): 4th-6th century, from southern China during the Wu Kingdom period

- Kan-on (漢音): 7th-9th century, from Chang'an (modern Xi'an), the capital during the Tang Dynasty

- Tō-on (唐音): 12th-16th century, from later Chinese dynasties

Each time, they kept the new pronunciations alongside the old ones! That's why many kanji have multiple on'yomi readings.

Take the character 明 (bright):

- Go-on reading: みょう (myō)

- Kan-on reading: めい (mei)

- Tō-on reading: みん (min)

Today, most common on'yomi readings come from the Kan-on group, but you'll encounter all types in everyday Japanese.

Examples Of On'yomi And Kun'yomi

Water

- Kun'yomi: mizu みず

- On'yomi: sui すい

- Words that use this kanji: mizu 水 (water), suiei 水泳 (swimming), suiyōbi 水曜日 (Wednesday).

The on'yomi is similar in pronunciation to shuǐ ("water") in Mandarin.

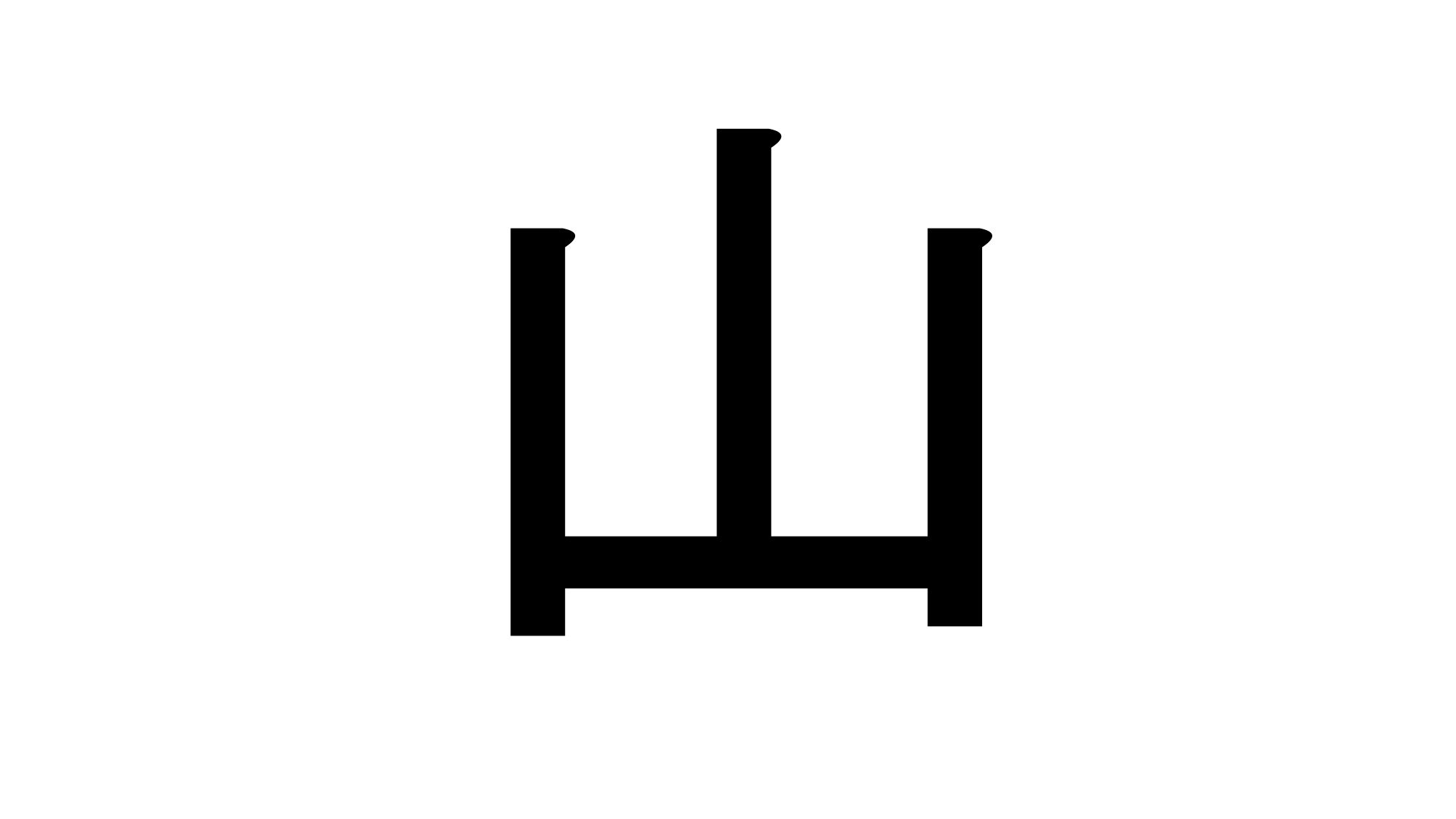

Mountain

- Kun'yomi: yama やま.

- On'yomi: san さん.

- Words that use this kanji: yama 山 (mountain), Fujisan 富士山 (Mount Fuji), sanchō 山頂 (summit of a mountain).

The on'yomi is similar in pronunciation to shān ("mountain") in Mandarin.

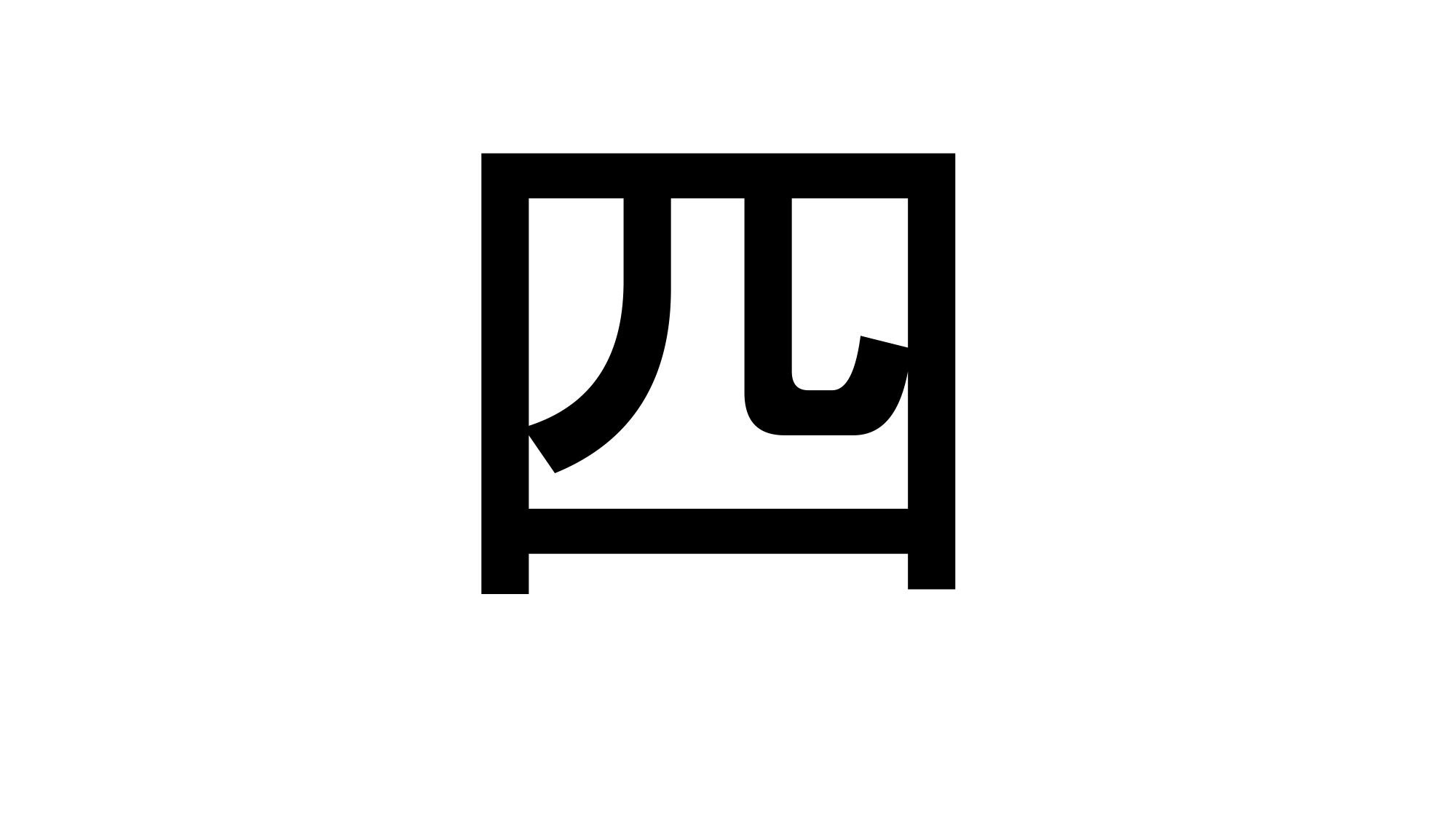

Four

- Kun'yomi: yon よん, yo よ, yo よっ.

- On'yomi: shi し.

- Words that use this kanji: shi/yon 四 (four), shigatsu 四月 (April), yoji 四時 (4 o'clock), yottsu 四つ (four objects).

The On'yomi is similar in pronunciation to sì ("four") in Mandarin.

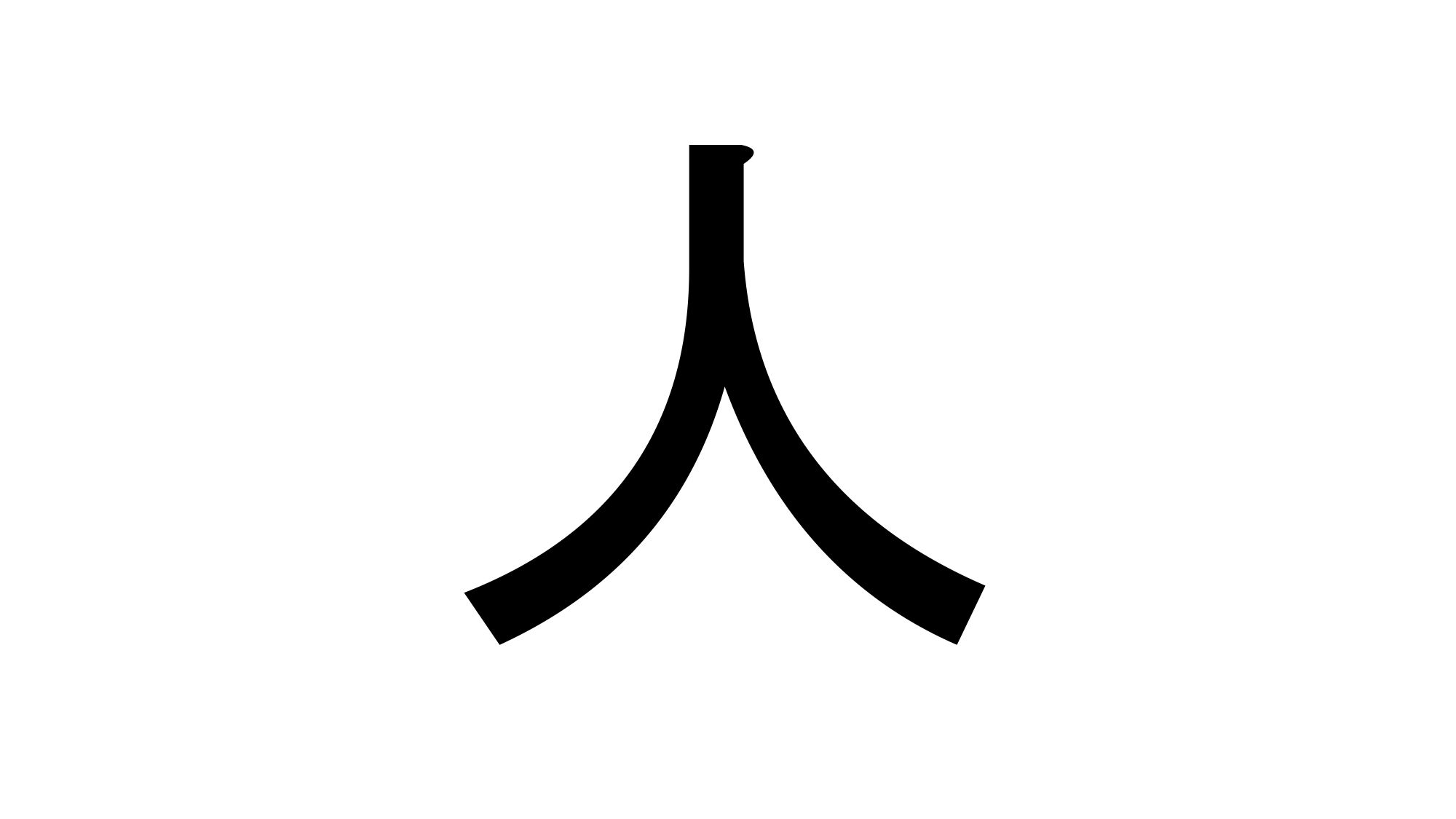

Person

- Kun'yomi: hito ひと.

- On'yomi: jin じん, nin にん.

- Words that use this kanji: hito 人, Amerika-jin アメリカ人 (American person), san-nin 三人 (three people).

Jin is similar to rén in Mandarin and nin in Wu or Shanghainese.

Not All Kanji Have Kun'yomi

While most kanji have both on'yomi and kun'yomi readings, there are exceptions that make learning Japanese even more interesting (or challenging, depending on your outlook).

Kanji With Only On'yomi Readings

Some kanji only have on'yomi readings because they represent concepts that didn't have specific single words in ancient Japanese, or they were imported for technical or academic purposes.

Common examples include:

- 茶 (ちゃ, cha) - tea

- 医 (い, i) - doctor, medicine

- 肉 (にく, niku) - meat

- 点 (てん, ten) - point

- 感 (かん, kan) - feeling

These kanji typically represent concepts that were either introduced to Japan from China or didn't have a single, unified term in native Japanese. For example, when the concept of tea was imported from China, the Japanese adopted both the drink and its name, rather than creating a new native word for it.

Kanji With Only Kun'yomi Readings

On the flip side, kanji that were created in Japan (kokuji) typically only have kun'yomi readings:

- 畑 (はたけ, hatake) - field

- 峠 (とうげ, tōge) - mountain pass

- 込む (こむ, komu) - to be crowded

- 匂い (におい, nioi) - fragrant

- 枠 (わく, waku) - frame

These characters were created to write native Japanese words that already existed but didn't have corresponding Chinese characters. The Japanese made these by combining parts of existing kanji to create new characters with meanings specific to Japanese culture and language.

When Should I Use Kun'yomi And On'yomi?

There isn't any rule for when using kun'yomi and on'yomi when reading kanji, but there is a pattern that helps. Most words that are written with only one kanji have a kun'yomi reading. For instance, mizu 水 (water), hi 火 (fire), hito 人 (person), ki 木 (tree), tsuki 月 (moon). All of these words have a kun'yomi reading.

As for on'yomi, most words that are written with two or more Kanji have this type of reading. For example, suiei 水泳 (swimming), san-nin 三人 (three people), shi-gatsu 四月 (April), kazan 火山 (volcano).

However, this is just a pattern and not a rule. There are some exceptions to these, and the only way to read these words is practice:

- suiyōbi 水曜日 (Wednesday): the last Kanji, 日, has a kun'yomi reading, whereas 水 and 曜 have both on'yomi.

- shigoto 仕事 (job, work): reading for 仕 is on'yomi and for 事 is kun'yomi.

In some cases, both readings are OK:

- yon/shi 四 (four).

- nana/shichi 七 (seven).

- mainen/maitoshi 毎年 (every year).

- maigetsu/maitsuki 毎月 (every month).

What's more, in some extreme cases, kun'yomi and on'yomi may change the word's meaning. For example, 市場 can be read with both kun'yomi and on'yomi, but the meaning of the word changes depending on the reading. The kun'yomi reading, ichiba, means "town or street market", whereas the on'yomi, shijō, means "stock market".

What Is Nanori?

Just when you thought you understood the kanji reading system with on'yomi and kun'yomi, there's actually a third type of reading that doesn't get talked about as much: nanori (名乗り). Nanori readings are special pronunciations used almost exclusively for names. The term "nanori" itself means "to state one's name" in Japanese.

These readings often don't follow the regular patterns of on'yomi or kun'yomi. They developed because names in Japan carry special cultural weight, and many families kept traditional readings for generations, even as the standard language changed around them.

Common Nanori Examples

Some kanji have several different readings when used in names:

- 一 (one): Usually いち (ichi) or ひと (hito), but in names can be かず (kazu), はじめ (hajime)

- 真 (truth): Usually しん (shin) or ま (ma), but in names can be まこと (makoto)

- 子 (child): Usually し (shi) or こ (ko), but can be ね (ne) in names

- 豊 (abundant): Usually ほう (hō), but in names often ゆたか (yutaka) or とよ (toyo)

- 美 (beautiful): Usually び (bi) or み (mi), but in names can be よし (yoshi)

Japanese names can use any mix of on'yomi, kun'yomi, and nanori readings, sometimes all in the same name!

Take the name 山田太郎 (Yamada Tarō):

- 山 (yama) is the kun'yomi reading

- 田 (da) is the on'yomi reading

- 太郎 (tarō) uses a special nanori reading

When you see a name written in kanji, there's often no definitive way to know how it's read unless you're told or it's written with furigana (pronunciation guides).

For example, the name 大輔 could be read as:

- Daisuke (most common)

- Taisuke

- Daiyū

- Several other possibilities

Fortunately, many Japanese business cards include the kana pronunciation of names precisely because kanji readings for names can be so unpredictable. To help you out further, here are patterns that can help:

- Common name suffixes for boys: 郎 (rō), 也 (ya), 輔 (suke), 彦 (hiko)

- Common name suffixes for girls: 子 (ko), 美 (mi), 香 (ka), 恵 (e)

- Family names with locations: 山 (yama), 川 (kawa), 田 (ta/da), 森 (mori)

What Is Ateji?

Think of it as a phonetic use of kanji, where the actual meaning of the characters becomes secondary or even completely irrelevant.

For example, the word for "coffee" in Japanese is written as 珈琲 (kōhī). These kanji were picked simply because they can be pronounced "kō" and "hī"—not because they have anything to do with coffee. (The first character actually means "ornament for hair" and the second means "to spend"!)

One of the most common uses of ateji is for foreign loanwords. Before katakana became the standard way to write foreign words, the Japanese often used kanji combinations based purely on sound:

- アメリカ (America): Originally written as 亜米利加

- ビール (beer): Written as 麦酒 (literally "barley liquor" - this one actually makes sense!)

- タバコ (tobacco): Written as 煙草 (literally "smoke grass")

Some of these ateji spellings were deliberately chosen to suggest meaning (like "beer"), while others were purely phonetic approximations.

Many place names in Japan also use ateji. The characters were chosen to match the pronunciation of existing place names:

- 横浜 (Yokohama): The kanji mean "side" and "beach"

- 秋葉原 (Akihabara): The kanji mean "autumn," "leaf," and "field"

These places weren't named for their kanji meanings—the kanji were picked to match the sounds of existing names.While modern Japanese typically uses katakana for foreign loanwords, you'll still find ateji in:

- Traditional company names

- Certain food and drink items

- Historical place names

- Some artistic or literary contexts

For example, 寿司 (sushi) uses kanji for "longevity" and "administrator," which have little to do with the food itself!

Learn To Read Kanji With Lingopie

Learning kanji readings might seem tough, but now you have the tools to make it work! We've covered how Japanese borrowed Chinese characters, creating on'yomi and kun'yomi. We've shown you which reading to use when, and looked at special cases like nanori for names and ateji for sound-based usage.

The best way to learn is:

- Start with one common reading per kanji

- Pick up new readings through real vocabulary

- Look for patterns instead of memorizing everything

- Practice regularly with actual Japanese content

Learning kanji takes time, but you'll soon be reading manga, watching anime, and exploring Japanese culture without translations!

Want to speed up your progress? Try Lingopie to watch Japanese shows with interactive subtitles that teach you kanji in real situations. Seeing how on'yomi and kun'yomi work in actual conversations makes everything click faster than studying with flashcards alone.

Start your journey today at Lingopie and turn your kanji confusion into reading confidence!

![How To Write The Japanese Kanji For Love [+ FREE Printable]](/blog/content/images/size/w300/2025/03/Japanese-Kanji-for-Love-1.jpg)

![10 Best Horror Anime For Learning Japanese [Guide]](/blog/content/images/size/w300/2026/01/Japanese-horror-anime--1-.jpg)